- Home

- Paul Alexander

Salinger

Salinger Read online

for Christopher Gines

for Lauren Alexander

for my family

and for James C. Vines III,

literary raconteur extraordinaire,

without whom this book would not exist

“Don’t you want to join us?”

I was recently asked by an acquaintance when he ran across me alone after midnight in a coffeehouse that was already almost deserted.

“No, I don’t,” I said.

FRANZ KAFKA

as quoted by Salinger in “Zooey”

Contents

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

PREFACE

A SIGHTING

TWO BIOGRAPHIES

SONNY

THE YOUNG FOLKS

INVENTING HOLDEN CAULFIELD

PRIVATE SALINGER

SYLVIA

SEYMOUR GLASS, ETC.

1950

THE CATCHER IN THE RYE

NINE STORIES

CLAIRE

THE GLASS FAMILY

HEROES AND VILLAINS

GOOD-BYES

JOYCE

THEFT, RUMOR, AND INNUENDO

STALKING SALINGER

TRIALS AND TRIBULATIONS

GHOSTS IN THE SHADOWS

CODA

ENDNOTES

INDEX

Acknowledgments

After he was prevented from publishing A Writer’s Life, his biography of J. D. Salinger, Ian Hamilton deposited his entire Salinger research file in the Department of Rare Books and Special Collections at Princeton University Library. Anyone can read the sizable file, which I did. As I studied the documents, I found much biographical material Hamilton had not used in writing In Search of J. D. Salinger, the book about the controversy that he produced when the courts blocked the publication of A Writer’s Life. I was also helped immensely by the New Yorker archive at the New York Public Library, which became open to the public after Hamilton published In Search of J. D. Salinger. Mine is the first book to use this important archive as source material. In addition, I did research work in or was supplied with research material by various libraries at Columbia University, New York University, and the University of Texas as well as the rare book and manuscript collection at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, the Gotham Book Mart, the Library of Congress Copyright Office, and the alumni offices at Harvard University and Yale University. In the Clerk’s Office in the county courthouse in Sullivan County, New Hampshire, I found Salinger’s divorce papers, which had not been studied by other biographers before. Finally, through various sources, I was able to piece together much of what was said in Salinger’s deposition in J. D. Salinger versus Random House and Ian Hamilton—the only formal interview for which Salinger has ever sat.

As for secondary sources, I read Advertisements for Myself by Norman Mailer, At Home in the World and Baby Love by Joyce Maynard, Chaplin by David Robinson, Charles Chaplin: My Autobiography by Charles Chaplin, Conversations with Capote by Lawrence Grobel, Dirty Little Secrets of World War II by James F. Dunnigan and Albert A. Nofi, The Fiction of J. D. Salinger by Frederick Gwynn and Joseph Blotner, The Films of Susan Hayward by Eduardo Moreno, Genius in Disguise by Thomas Kunkel, Goldwyn by A. Scott Berg, Here at the New Yorker by Brendan Gill, Here But Not Here by Lillian Ross, In Search of J. D. Salinger by Ian Hamilton, J. D. Salinger by Warren French, J. D. Salinger by James Lundquist, J. D. Salinger: An Annotated Bibliography by Jack R. Sublette, J. D. Salinger and the Critics edited by William Belcher and James Lee, The Journals of Sylvia Plath by Sylvia Plath, Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov, Louise Bogan by Elizabeth Frank, Modern European History by John Barber, Salinger: A Critical and Personal Portrait edited by Henry Grunwald, Salinger’s Glass Stories as a Composite Novel by Eberhand Alsen, Translate This Darkness by Claire Douglas, Trio: The Intimate Friendship of Carol Matthau, Oona Chaplin, and Gloria Vanderbilt by Aram Saroyan, United States by Gore Vidal, What I Know So Far by Gordon Lish, A Writer’s Life (galleys only) by Ian Hamilton.

Several magazine articles were of great value, among them “In Search of the Mysterious J. D Salinger” by Ernest Havemann (Life, November 3, 1961); “J. D. Salinger” by William Maxwell (Book-of-the-Month Club News, July 1951); “The Private World of J. D. Salinger” by Edward Kosner (The New York Post Magazine, April 30,1961); “Sonny: An Introduction” (Time, September 15, 1961); “Tiny Mummies!” and “Lost in the Whichy Thicket” by Tom Wolfe (New York, April 1965); “What I Did Last Summer” by Betty Eppes (The Paris Review, 1981). For their interviews, research material, or other help, I’d like to thank William Abbe, N. Wade Ackley, Paul Adao, Roberta Adao, Mark Alspach, A. Alvarez, Roger Angell, William Avery, Alex Beam, John Calvin Batchelor, A. Scott Berg, Naomi Bliven, Harold Bloom, Andreas Brown, Troy Cain, Robert Callagy, Ann Close, Kathy Constantini, Richard D. Deitzler, Elizabeth Drew, James Edgerton, Leslie Epstein, Clay Felker, Ian Frazier, Dorothy B. Ferrell, Warren French, Frances Glassmoyer, Robert Giroux, Jonathan Goldberg, Richard Gonder, Lawrence Grobel, Leila Hadley, Ian Hamilton, Lianne Hart, Edward W. Hayes, Susie Gilder Hayes, Samuel Heath, Anabel G. Heyen, Franklin Hill, Rust Hills, Phoebe Hoban, Russell Hoban, William H. Honan, A. E. Hotchner, Peter Howard, Robert Jaeguers, Burnace Fitch Johnson, Richard Johnson, Elaine Joyce, Frances Kiernan, Mary D. Kierstead, Edward Kosner, Thomas Kunkel, Penny Landau, Robert Lathbury, Gordon Lish, Rebecca Lish, Mary Loving, Gigi Mahon, Ved Mehta, Daniel Meneker, Sylvia Miles, Gloria Murray, Norman Nelson, Ethel Nelson, Katrinka Pellechia, George Plimpton, Paige Powell, Ron Rosenbaum, Jennifer Lish Schwartz, Jonathan Schwartz, Al Silverman, Dinitia Smith, Michael Solomon, Charles Steinmetz, Roger Straus, Gay Talese, Joan Ullman, Amanda Vaill, Gus Van Sant, Daniel White, Maura Wogan, Tom Wolfe, and Ben Yagoda. For his friendship and advice I’d also like to acknowledge James Ortenzio, someone who’s always there when he’s needed.

While I worked on this book, I wrote “Talk of the Town,” an article about Lillian Ross and William Shawn, and “J. D. Salinger’s Women” for New York, where I’m lucky to have John Homans as my editor. It takes years to write a book, so as I’m working on one I often write for magazines. I’d like to thank my editors at the various publications I work for who have supported me while I’ve written this book—Laurie Abraham, Tom Beer, Richard Blow, Robin Cembalest, Lisa Chase, Will Dana, Jessica Dineen, Milton Esterow, Erika Fortgang, Mark Horowitz, Lisa Kennedy, Robert Love, Caroline Miller, Roberta Meyers, Nancy Novograd, and Maer Roshan. At Renaissance Books, I’d like to thank Bill Hartley and Richard O’Connor as well as Arthur Morey whose notes, insights, and suggestions were invaluable. Finally, I want to express my gratitude to Betsy Cummings for assisting me in researching Salinger’s life and work.

Preface

When J. D. Salinger created Holden Caulfield during the 1940s (he worked on some form of The Catcher in the Rye for ten years before it was published in 1951), he had few models to look to. As critics have pointed out, the one character comparable to Holden in earlier American literature is Huckleberry Finn in Mark Twain’s classic The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Holden is on a quest through New England, and then New York City, much as Huck is on a quest on the Mississippi River. Holden encounters the ugliness of the adult world much as Huck confronts the shocking reality of racism and bigotry. Huckleberry Finn is the seminal coming-of-age novel in nineteenth-century American literature; The Catcher in the Rye occupies a similar place in the literature published after 1950.

Salinger has become such a notable literary figure that he actually appears as a character in W. P. Kinsella’s Shoeless Joe, the novel on which the picture Field of Dreams was based, but his importance can best be measured in the way Catcher has influenced books that have been written after it. Last Summer by Evan Hunter, The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath, The Last Picture Show by L

arry McMurtry, The Basketball Diaries by Jim Carroll, A Separate Peace by John Knowles, Birdy by William Wharton, Less Than Zero by Bret Easton Ellis, Bright Lights, Big City by Jay McInerney, Girl, Interrupted by Susanna Kaysen—these are just a few books written in the tradition of The Catcher in the Rye.

But Salinger’s novel has had an effect on areas of American society besides literature. As the rebellious 1950s gave way to the radical 1960s, a youth culture emerged in the United States. That “youthquake,” as some have called it, continued to define American popular culture during the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s. Because of this, Catcher has had an impact on different parts of American culture. A host of films—Rebel Without a Cause, American Graffiti, Dead Poets Society, Summer of ’42, Stealing Home, Risky Business, Running on Empty, Dirty Dancing, I Never Promised You a Rose Garden, The Graduate, Stand By Me, and Fast Times at Ridgemont High are only a few—could not have been made in the way they were if Catcher had not existed as a model before them. Indeed, one could argue that the entire teen-movie subgenre, which has become a staple of the film industry in Hollywood, owes a debt to Holden and Catcher. So does much of television’s youth-oriented programs, as exemplified by series like The Wonder Years, James at 15, My So-Called Life, Dawson’s Creek, and Felicity. And how different is the angst articulated by Holden from that expressed in the music and lyrics of Green Day or Jewel or Smashing Pumpkins? Is there any area of American popular culture that’s not been touched by Holden and what he has come to represent?

With Holden, Salinger prefigured the juvenile delinquency of the 1950s, the “drop-out” mentality of the 1960s generation, and the general disquiet among much of today’s youth. With Holden, Salinger foresaw the generation gap that emerged in the 1960s and, to a certain extent, never disappeared. Holden has become, then, a lasting symbol of restless American youth. Today, Holden’s nervous breakdown at the end of the novel seems absolutely contemporary in a society whose youth are as troubled, as jaded, and yet as defiantly hopeful, as they ever have been before. Consequently, it would be hard to overestimate the importance of the contribution Salinger made to American culture when he decided to write a novel about this “crazy” neurotic boy who flunks out of prep school, sets out on a short but strange odyssey to avoid going home to confront his parents, and, as he does, learns fundamental lessons about life, loss, and self.

A Sighting

It was a beautiful afternoon in early October 1994 and I had driven up from New York City to Cornish, New Hampshire, a town which for all intents and purposes does not exist. There are no business establishments to speak of in Cornish, only a general store on the side of the road and, not too far away, a white wooden meeting house situated near a building that serves as the volunteer fire department headquarters. Indeed, in Cornish, the only element of a town that does exist is a scattering of houses built here and there among the rolling wooded hills. Of course, the most asked-about house of all of these, I discovered once I found it, could not be seen clearly from the dirt road that passed by the entrance to its driveway, an entrance marked by two prominently displayed NO TRESPASSING signs. The house, true to the press reports that have been published about it through the years, is of a chalet style. It is neither cramped nor ostentatious but functional, and in October 1994 it had been, for well over two decades, the home of J. D. Salinger, the great American novelist and recluse. While I sat in my car on the side of the road and looked up at the house, much of which was blocked by foliage, I had the strangest feeling. What I felt—even though I could not confirm it—was that as I was watching the house someone inside it was watching me.

I had been given the general directions to Salinger’s house by a woman known locally as the Bridge Lady. The Bridge Lady had acquired her name because over the years she had spent inordinate amounts of time at her own instigation during the spring, summer, and fall in a makeshift information booth near the covered bridge that spans the Connecticut River to connect Cornish with Windsor, Vermont, a town that does exist since it has its share of stores, restaurants, public buildings, gasoline stations, and the like. The covered bridge in question is the longest one in the country, so the Bridge Lady has been able to create a sort of purpose for herself by recounting a history of the bridge for tourists who stop at her information booth. Since the Bridge Lady and her husband worked for Salinger in the early 1960s (she was the housekeeper, he the groundskeeper), she talked with me about him a bit, although she was reluctant to give me specific directions to his house. Instead she told me, somewhat vaguely, to look among the dirt roads that wind along one particular mountain. Naturally, almost all of the residents of Cornish know the directions to Salinger’s house. Over time, countless tourists have asked about it, just as they have inquired about other local attractions, such as the covered bridge.

Once I located the house, I retraced the route and noted the directions so that I could find it again in the future. On that cool autumn day in October, I turned left coming off the covered bridge from Windsor and drove down the main road that wound along the river. On my right I passed a side road which, a sign informed me, lead to the Saint-Gaudens Historical Site. Soon, I passed a green historic marker commemorating the old Cornish Colony. The marker stood near the Blow-Me-Down Mill, a three-story stone structure with wood siding. Past the mill, at the Chase Cemetery, a small graveyard surrounded by a white picket fence, I turned right onto a narrow asphalt road. Next I drove just over a mile, passing a three-story slat-shingled mansion and then two huge red barns built among green sloping hills, until I turned right at a small abandoned guard house.

Going up the asphalt road, I passed Austin Farms. Just beyond the farms, the asphalt road turned into a dirt road, which then ran under a long heavy canopy created by rows of tall green trees growing on either side of the road. In time, to my left, I saw a red house that appeared to be a converted barn. Next, continuing up the road, I topped a hill, which was bordered by spacious pastures—pastures, I later learned, that belonged to J. D. Salinger. Driving up the road, I stopped at an old dilapidated barn. Finally, I looked up through the trees on the hill in front of me and I saw it—Salinger’s house. Looking about, I noticed several signs displayed here and there on posts and trees. It was the same sign I would see on the two trees next to his driveway. The sign read:

POSTED

PRIVATE PROPERTY

HUNTING FISHING TRAPPING OR TRESPASSING

FOR ANY PURPOSE IS STRICTLY FORBIDDEN

VIOLATORS WILL BE PROSECUTED

I had come here on this day in October to sit in my car on the side of the dirt road and look up at the house on the hill because the man who lived there had written The Catcher in the Rye, and because, since the publication of that book in 1951, he had lived his life in such a way as to make locating his house a noteworthy event. Why this has happened, why through the years a steady stream of admirers has made its way to Cornish, says a lot about fame and celebrity and, more specifically, the manner in which American society has come to glorify fame and celebrity in the latter part of the twentieth century. Most importantly, it also says something about the enduring power of art. For this much is true without question: If Salinger had not written a masterpiece that ranks among the best of its genre ever to be written, if he had not also written a group of stories that stand among the most original produced by any American author, few fans, including myself, would have made such an effort to find the house on the hill where he lives.

None of this was on my mind that afternoon in October 1994 as I sat in my car and looked up at his house. I only knew that I loved some of his stories and all of The Catcher in the Rye, that I found the Salinger myth strangely appealing, and that, because of these two facts, I had gotten in my car this morning in New York City, driven some two hundred and sixty miles to Cornish, New Hampshire, and searched Cornish’s dirt roads until I found the house I knew to be his. Then, while I sat there with the car windows down, I suddenly heard the faint sound of gravel crackling under the weigh

t of tires. Slowly the sound became louder and louder until I saw a car emerge from the thicket of trees to head down the hill and stop at the driveway’s entrance. When I looked more closely, when I focused my attention on the car’s driver, I saw who it was—Salinger himself. After pausing at the driveway’s entrance, he pulled out onto the dirt road. It was then I could see him best. Haggard, hunched-over, his hair white and thinning, he looked like a very old man. If Holden Caulfield is frozen in time, always the youthful, evanescent teenager, his creator clearly was not; it was shocking to witness Salinger in his mid-seventies. Finally, as I continued to stare, as I thought to myself that I was looking at J. D. Salinger, he accelerated the car, and, leaving as quickly as he had appeared, he was gone.

Two Biographies

In the careers of most modern and contemporary writers, a pattern of activity emerges. After the writer establishes himself, he produces his work, and periodically, about every three or four years, he releases that work by way of a publisher to the public. There are exceptions, since publishing-industry norms may or may not serve idiosyncratic writers. The author may be less prolific, as in the case of F. Scott Fitzgerald, because he struggles with a piece of writing for years before he can let it go. Or he or she may write only one book, which ends up being a masterpiece, as Harper Lee did with To Kill a Mockingbird. Or the author may die before the public comes to appreciate the full genius of his or her work, as was the case with Sylvia Plath. However, most authors, even those inspired by true genius, write and publish on a regular basis, primarily because they want to communicate with an audience. In all likelihood, that same impulse forces the writer to make himself available to his readers in the various ways writers have access to—by giving readings, for example, or answering fan mail. After all, should an author be successful, it is the readers, the people who buy the books, who allow him to enjoy the success he has achieved.

Rough Magic

Rough Magic Dark Star

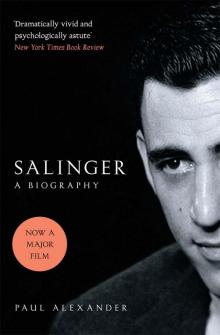

Dark Star Salinger

Salinger